Sextortion: The Hidden Pandemic

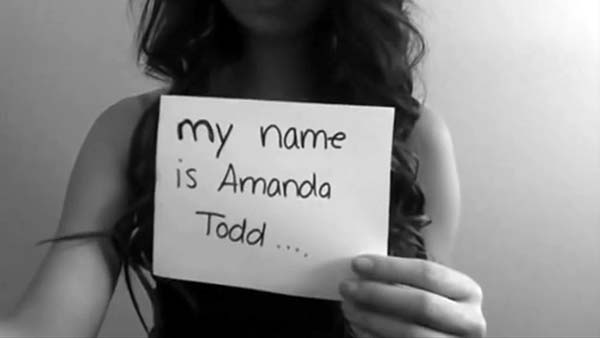

Amanda Todd tells her harrowing, “never-ending” story about being a victim of sextortion to warn other children – without ever saying a word. Instead, the 15-year-old holds up flashcards, and the words she’s written on them become more painful to read as she works her way through the stack in her hands.

A chance meeting in a chat room on the internet would send Amanda, then a 13-year-old, spiraling to the depths of depression over the next two years and make her the target of cruel cyberbullies. Her new online friend had told her she was “stunning, beautiful, perfect” and convinced her to flash her breasts on her webcam. He later threatened her to “put on a show for me” or he’d share the topless image online with everyone she knows. He was true to his word.

A month after sharing her story on YouTube, Amanda’s pain became unbearable. She ended her life at her home in Canada on Oct. 10, 2012. Her video instantly went viral, and millions of people learned about sextortion which was, at the time, a relatively new kind of online enticement. Today, nearly 10 years later, reports of sextortion to our CyberTipline have skyrocketed here at the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. (NCMEC)

Now a powerful new documentary, “Sextortion: The Hidden Pandemic,” shows how child predators target their victims on the internet and tells the story of a Navy Top Gun pilot who groomed hundreds of children all over the world and extorted them for explicit sexual images. The film will have its world premiere at the prestigious Santa Barbara Film Festival on March 3. The producers have dedicated their documentary in memory of Amanda Todd and to all victims of sextortion.

The documentary, which was produced by the award-winning Auroris Media production company, highlights one of the largest international sextortion cases investigated by Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) and the Justice Department. The film was also done in partnership with NCMEC and will be available for wide distribution later this year.

“Everyone should watch this documentary,” said John Shehan, vice president of NCMEC’s Exploited Children Division. “Sexual predators have found a way to extort children in the privacy of their homes. They don’t need a key to get in; just a device connected to the internet. They secretly coerce their underage victims to produce sexual images, to have sex with them or give them money.”

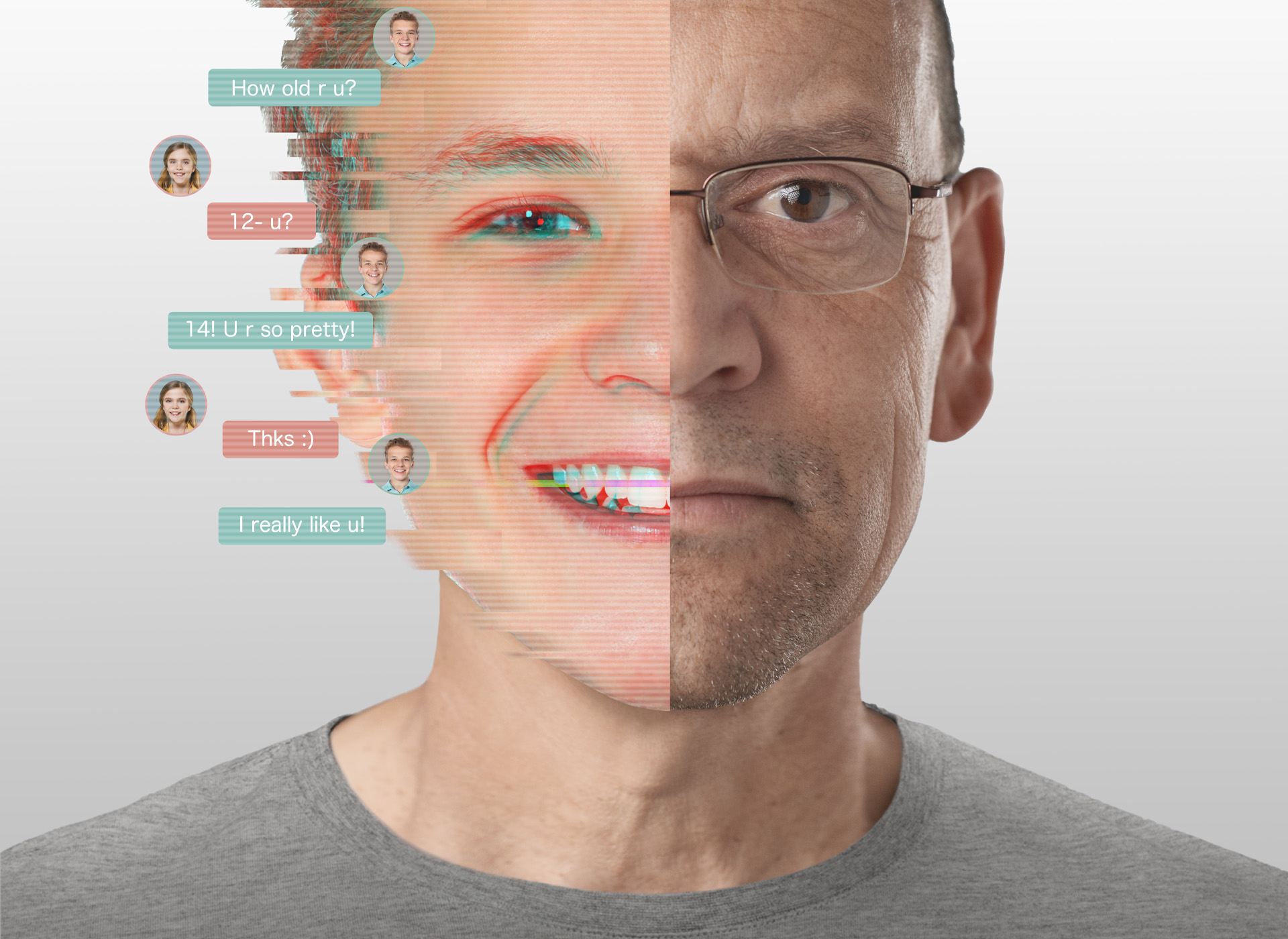

The producers, Maria and Stephen Peek, first heard about sextortion in 2019 and the devastating impact it was having on children. They learned how child predators, often posing as teenagers, have become expert at grooming children they meet online, making them feel special and loved. Once they gain their trust, they then threaten to not only share their sexually explicit images online if they don’t comply with their demands but to harm their families if they dare tell anyone.

The more the couple read about this growing threat on the internet, they knew they had to help get the word out. As the parents of two daughters, 10 and 13, they realized their children were in the highest-risk age group being targeted by child predators on the internet.

“It was very personal for us,” said Stephen, who knew many parents, like them, did not realize this was happening to both girls and boys on the internet, often in their own homes. “We knew this story had to be told.”

It wasn’t easy. Visually showing child sexual exploitation in any medium is difficult considering the age of victims and the sexual nature of the crime. But making a documentary in the throes of a pandemic compounded those challenges, yet the producers felt an urgency to tell this story.

Maria, who also directed the documentary, said entire buildings had to be shut down over Covid concerns for interviews with those who investigated and prosecuted the Navy pilot. As the trial unfolds in the film, victims’ initials were used to protect their identities, and an artist was hired to do courtroom sketches from trial transcripts which were then animated, she said.

“We reached out to NCMEC early because we knew the nonprofit organization was on the front lines of this fight,” said Stephen, who along with Maria interviewed Lindsey Olson, executive director of our Exploited Children Division, about the scope of the problem.

Lindsey is interviewed for the documentary at NCMEC headquarters in Alexandria, Virginia.

Here at NCMEC, we operate the CyberTipline, the centralized mechanism in the U.S. for the public and Internet Service Providers to report suspected online child sexual exploitation. Since we began operating it in 1998, we’ve received more than 116 million reports, a staggering number that has increased exponentially in recent years, 29 million in the last year alone.

Our reports of online enticement, which includes sextortion, have dramatically spiked, increasing 98% from 2019 to 2020, part of an upward trend. In 2018, there were 12,070 online enticement reports to our CyberTipline and by 2021 there were 44,155.

“From what we’ve seen, it only stops when the child either tells an adult or the offender is identified in some sort of law enforcement investigation,” said Lindsey, during an interview for the documentary. “Unfortunately, these cases can have really tragic consequences. Kids can become depressed, and we’ve even seen some cases where children have taken their own lives.”

Erin Burke, unit chief of the Child Exploitation Investigations Unit at Cyber Crime Center (C3), part of HSI, said that since she began working to combat child exploitation in 2007, sextortion cases have “drastically shot up,” in great part because of how easily accessible the internet is now to all ages.

In chat rooms and forums online, child predators are now teaching each other the tools and tricks of the trade – how to target kids, how to groom them, how to evade law enforcement, said Erin, who is interviewed in the documentary.

“The deviancy is getting worse,” Erin said. “Now it’s causing kids to cut or kill themselves. We’re out there trying to stop it.”

The unit chief said she believes prevention is key to helping unsuspecting children from falling victim to these relentless child predators.

The producers said there’s prevention material for elementary students but not a lot for middle and high school students who are most at risk. They’re working with HSI and NCMEC to use parts of their documentary to create resources that can be shared in schools “to save the next kid” and have created a discussion guide on their website at www.sextortionfilm.com.

Carol Todd, mother of Amanda, explains in the documentary how she found out her daughter was being sextorted in December 2010 after receiving a link with a photo of her daughter shirtless that was further linked to an adult pornography site. Amanda’s friends also received the photo and called police, who showed up at Carol’s home in Canada for a safety check.

At first, Carol said her daughter wouldn’t talk much about it until the photo was shared throughout their community. Then the cyberbullying started with a vengeance, so they moved her from school to school but the child predator would always find Amanda and continue to torment her and share photos with her new friends.

(To watch Amanda’s YouTube video, go to https://youtu.be/vOHXGNx-E7E)

The man facing charges in Amanda’s case, including extortion, Aydin Coban, 42, was convicted in the Netherlands on charges unrelated to Amanda’s case and was extradited to Canada in December to stand trial this summer. He has denied the charges.

After Amanda ended her life, Carol Todd, an educator, started the Amanda Todd Legacy Society, www.amandatoddlegacy.org, to spread awareness about sextortion and cyberbullying. She said that if her daughter had not made the YouTube video, her story would not have been shared around the world. It would have been a suicide, she said, something people don’t talk about.

“There weren’t many stories out there,” said Carol. “I became interested in sharing Amanda’s story so kids wouldn’t fall into the same trap. It became my life’s work.”