His Name Was Billy

The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children has more than 700 cases of deceased children with no names. John Parker Doe was one of them.

His skeletal remains were found by chance on Oct. 27, 1985, on a sprawling ranch in Parker County in the Dallas-Fort Worth area. A father and son were walking the remote property, hoping to find a potential home site. Instead, they were stopped in their tracks by a startling discovery: a murder scene.

The victim, a young male, believed to be between the ages of 15 and 20, was shot to death. His shallow grave, partially concealed under a tree and low brush, had been dug up by animals. Clothing, including a pair of “Guess” blue jeans and a “Union Bay” white fleece jacket, were strewn over a wide area.

The Parker County Sheriff’s Department knew if it was ever going to figure out who killed John Parker Doe, learning his identity was key. As the years went by, the case grew colder. With the passage of time, however, tremendous strides were being made in the use of DNA and technology in criminal investigations.

The sheriff’s department and the Tarrant County Medical Examiner’s Office in Texas worked closely with NCMEC and its technology partners over the years to try many of these new advances, including facial reconstruction, DNA phenotyping and genealogical testing.

Their big break finally came on Nov. 16, 2019 – 35 years after the discovery of John Parker Doe.

Sgt. Ricky Montgomery got the cold case in 2000 and tried everything to learn the identity of his young victim. He checked missing person reports that NCMEC sent him. He chased leads. Still no answers.

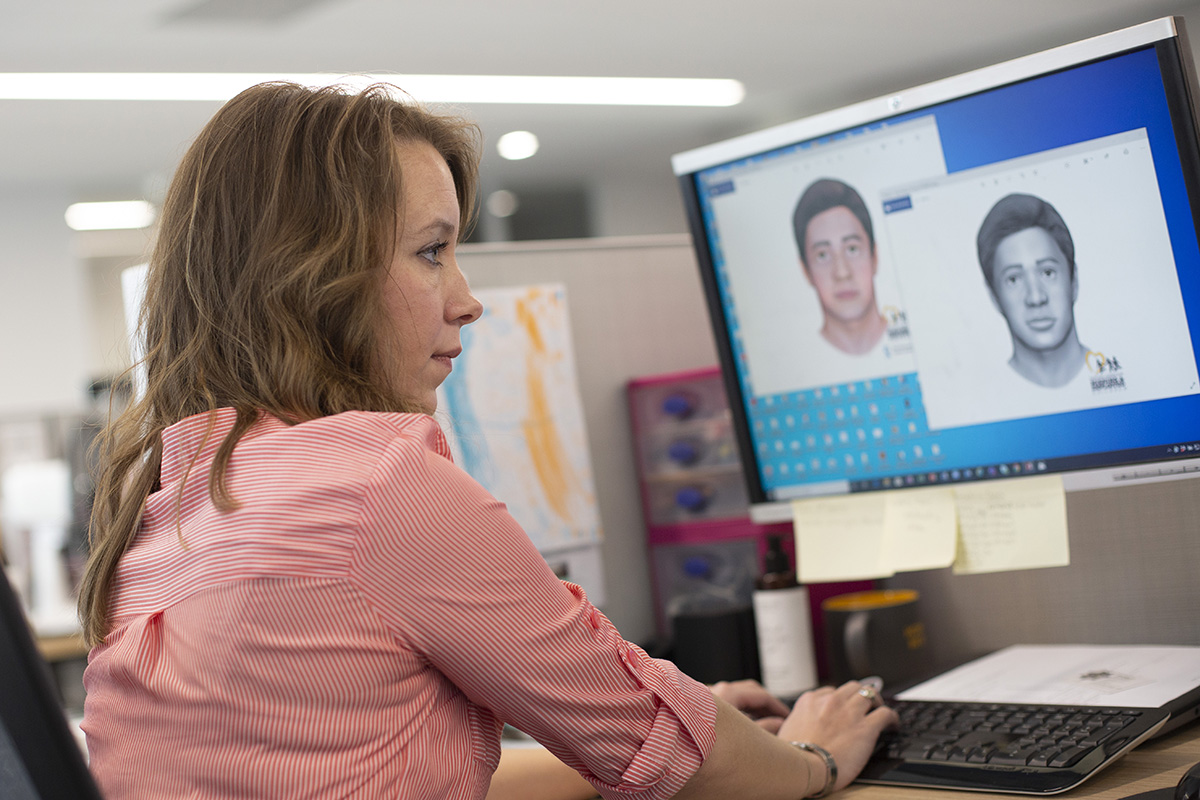

In 2002, Dr. Dana Austin, a forensic anthropologist with the Tarrant medical examiner’s office, reached out to NCMEC. Our forensic artist Joe Mullins did a 2-D computerized facial reconstruction of John Parker Doe’s skull in the hopes that someone might recognize him. It wasn’t the first time. An earlier clay facial reconstruction done in Texas did not yield an identification.

Nine years later, in 2011, NCMEC created a new Forensic Services Unit to focus on more than 700 unidentified deceased children cases. The unit began reaching out to law enforcement, coroners and medical examiners around the country for biometrics – DNA, fingerprints and dentals, a massive undertaking.

Ashley Rodriguez, a forensic case manager on the team, was assigned the John Parker Doe case. In 2013, she deployed two NCMEC consultants to Texas, both retired law enforcement officers, to review the cold case with fresh eyes. Part of their goal was to collect biometrics so that NCMEC could evaluate how advances in technology might help.

Four years later, NCMEC entered into a partnership with Parabon NanoLabs. The company had developed a process called Snapshot Phenotyping which uses DNA to determine traits including eye, hair and skin color, facial features, any freckling and ancestry.

Rodriguez thought the John Parker Doe case might be a good candidate. The first step was to bring in two of NCMEC’s existing partners, Bode Technology and DNA Solutions, for DNA extraction and sequencing, respectively, from the victim’s fibula.

The results were sent to Parabon, and through its DNA phenotyping, John Parker Doe’s face finally began coming into focus: He had very fair or fair skin, brown or hazel eyes, brown or black hair, zero or few freckles and was 98.4% of European ancestry.

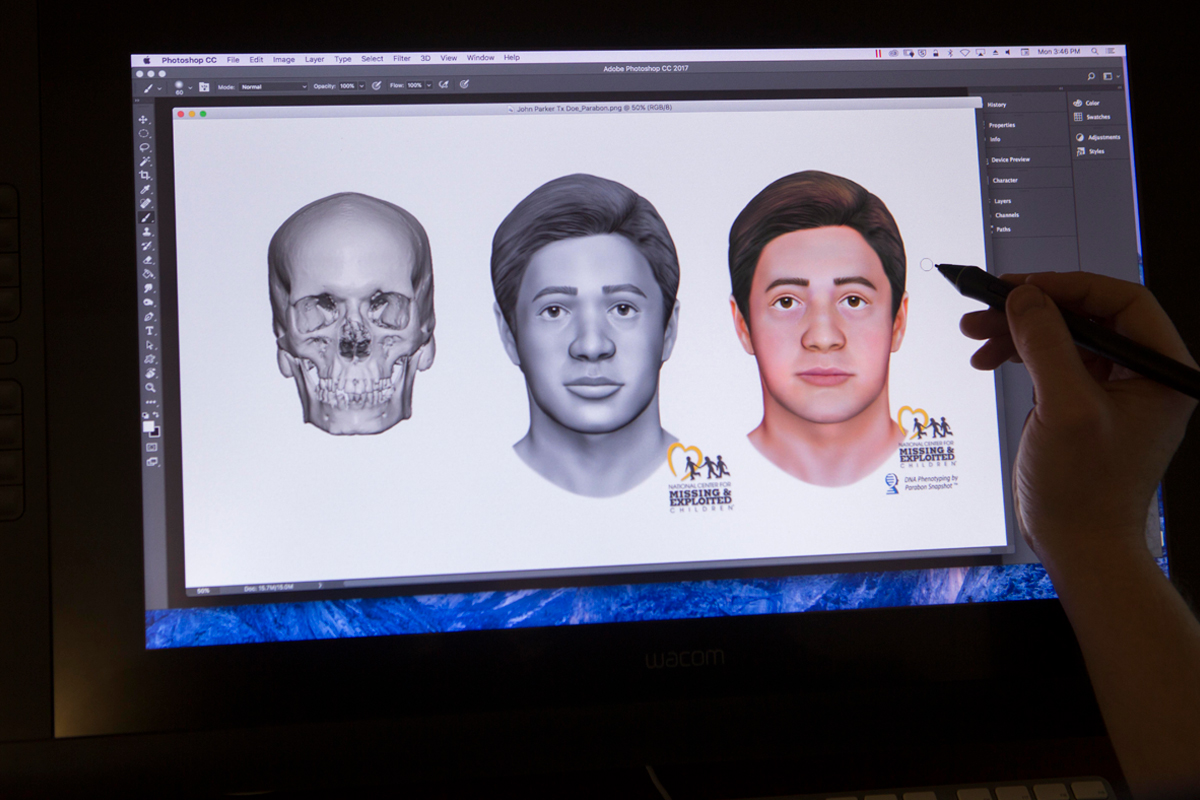

With this new information, NCMEC could create a more accurate picture of John Parker Doe. By this time, NCMEC was doing more advanced 3-D facial reconstructions, and this would be the first ever done in color. Using a CT-scan of the skull, and the analysis from Parabon, Colin McNally, supervisor of NCMEC’s Forensic Imaging Unit, began building the face, letting the skull on his computer screen guide him.

Following the contours of the bones, he placed 24 tissue-depth markers all over the skull so he’d know how to uniquely shape the face. No two skulls are alike.

Just as he would use clay to make a sculpture, McNally used “digital clay” to build the face on his computer. Using the tissue markers as a guide, he sculpted the tissue first, then the muscles and the nose. The ears and the hairstyle had to be generic, otherwise he’d be guessing. Then he moved to the eyes and the muscles in the neck.

After two long weeks of work, McNally was no longer looking at a skull on his computer screen. John Parker Doe was staring back at him – in living color.

NCMEC sent the facial reconstruction to the media, and Evidence Technology Magazine featured a NCMEC article about the case on its cover. Despite all this publicity, no one stepped forward to identify John Parker Doe.

Undaunted, the detective with Parker County wondered about another emerging field: genetic genealogy analysis. Genetic DNA test kits, such as Ancestry.com and 23andme, were becoming wildly popular with the public and creating a robust database of family history in GEDmatch, where people upload their DNA results and can search for birth parents and ancestors.

CeCe Moore, chief genetic genealogist for Parabon, did an initial assessment and got very excited, thinking this should be easy. It was anything but. What she thought could be done in a matter of weeks stretched over 18 months. She devoted hundreds of hours of her own time, determined to solve the mystery.

“I was working hundreds of other cases, but I couldn’t let him remain nameless,” said Moore. “The detective was committed to this case. He had worked so long for so many years. I didn’t want to let down the agency or NCMEC.”

The hope was to find a first or second cousin of John Parker Doe, who would share a set of grandparents with him. That way she could build the cousin’s family tree using DNA matches and public records and hopefully identify John Parker Doe.

She searched GEDmatch, but the potential first and second cousins she initially identified were adopted, not blood relatives. She kept trying to build trees but hit more roadblocks, including discrepancies between public records and genealogy.

Moore teamed with another genealogist, Cheryl Stedtler, who just happened to be working with the same two adopted cousins, looking to trace their birth parents. It soon became clear: the genealogists needed to first solve the adoptees’ cases in order to get answers in the John Parker Doe case.

One of the adoptees found his possible birth father but couldn’t confirm it through DNA because the man was deceased. Luckily, the man’s son agreed to take a DNA test and upload the results to GEDmatch.

It turned out he was a first cousin to John Parker Doe! It was the first real break in the case. Moore could now start building the family tree and searching for a male of the right age who was missing. She found one listed in the New York birth index. His public record vanished as he entered his 20s.

“That’s when I got very excited; I knew we’d found him,” said Moore. “It took some luck, it took some work, it took commitment to these adoptees. It really was one of the most difficult cases I ever worked.”

His name was Billy. Billy Fiegener.

Now Detective Montgomery could begin figuring out who killed Billy and why. Montgomery learned from Moore’s research that Billy was born in Brooklyn and would have been 22 when he was killed. Montgomery was then able to trace Billy’s parents to Florida, and he flew there to meet with them.

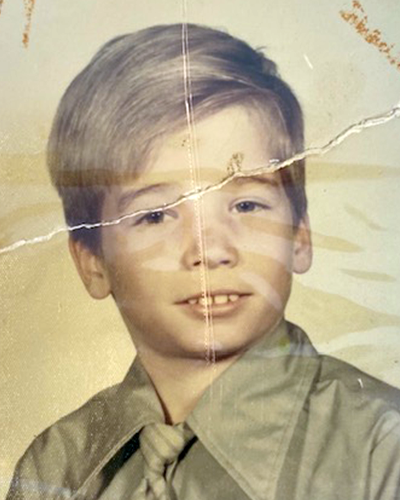

The family provided a DNA sample, which further confirmed it was Billy. The only photo they had of him was from grade school. Hurricane Sandy had destroyed all the others when they were living in New York.

Billy had been getting in serious trouble in Brooklyn, his parents said, and they sent him to work on a horse ranch in California owned by a former neighbor. They never knew what happened to him after that.

Montgomery was determined to find out. He tracked down relatives, including a brother who still lived in Brooklyn, and people who worked with him on the California ranch, slowly piecing together the story of Billy’s short life.

While working on the ranch, Billy had met a guy named Forrest Ethington who lived in the Dallas area. He was putting together some “crews” around the country to do coin shop heists.

They pulled off some coin shop heists together in Texas, and then Billy decided to do some robberies on his own, Montgomery learned. But he got caught, and Ethington worried that Billy would turn on him to save his own hide.

Ethington told a witness he was going to have to kill Billy to silence him, Montgomery said. That’s when he marched Billy out to a remote part of the Texas ranch and shot him once in the back of the head.

Montgomery was ready to serve Ethington with a murder warrant and tracked him to a prison where he was serving time. But Ethington had died of a heart attack one month earlier at age 81.

The 35-year-old murder case of John Parker Doe could finally be closed, and Montgomery was grateful he could get answers to his family.

“I had so much help,” said Montgomery. “We were partners with NCMEC and Parabon. I don’t think any of us could have gotten anywhere without the other.”