For Officer, Missing Kids With Autism Hits Home

Danny, a 13-year-old boy with autism, was reported missing about 9:30 p.m. one night in Addison, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago. Even before police could respond to the urgent 911 call, Addison Police Sgt. Stefan Bjes knew exactly where to find him – about 1½ miles from his home.

The child, who is nonverbal, was safely back home within 10 minutes.

“I knew he’d go back to his old elementary school,” said Bjes, who was working an off-duty detail but heard the radio traffic and sent his officers to the school. “We had his mom come to the scene. We told her, ‘We’ve got him, he’s safe.’ We just waited for her to get there.”

Bjes, who has three sons, two with autism, knows from personal experience that nearly half of children on the autism spectrum will repeatedly wander, or bolt, from safe environments. In an instant, they’ll dash toward something they’re drawn to – often a body of water like a lake, a pond or a pool but also very specific things such as a highway sign, train tracks or, in Danny’s case, his elementary school. During wandering incidents, children on the autism spectrum who can’t swim may enter the water or step into traffic without fear, often with deadly consequences.

Here at the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, 354 children on the autism spectrum were reported missing to us last year, a 47 percent increase from the year before and all considered critically missing. (www.missingkids/theissues/autism). The actual number of wandering incidents is believed to be significantly higher, but many parents don’t call police, conducting their own searches, or the incident ends quickly or tragically, according to Lori McIlwain, co-founder of the National Autism Association (NAA). About a third of wandering cases tracked by the NAA resulted in death or the need for medical attention, most from accidental drowning followed by traffic fatalities, she said.

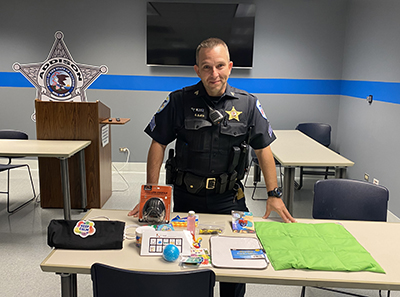

Sgt. Stefan Bjes says sensory kits can help calm children with autism.

Bjes, who trains officers how to respond to a call for a missing child with autism, fervently believes these tragedies are preventable and has taken a uniquely proactive approach. Working closely with their schools, his police department has established a registry for children with special needs that details critical information, including things they’re attracted to and triggers, such as sensitivity to sounds or light, that can set off an emotional meltdown. Officers are issued special aids, including flash cards and sensory kits, to communicate with children who are non-verbal.

“He’s being very proactive and cultivating a model for other states to follow,” said NAA’s Mcllwain, who also has a son with autism. “He’s a dad and a police officer so he can speak from both sides. What he’s doing should be replicated in other states, other communities.”

Danny had recently been added to the registry, which is how Bjes knew he’d head to his former school and would have to cross a busy highway in the dark to get there. A school social worker had heard about the police department’s “Premise Alert Program” and helped get Danny registered.

But it’s not a matter of just filling out a form, Bjes said. Many parents who have children with special needs distrust the police, terrified they’ll be perceived as negligent if their children frequently run away or that police will misconstrue their child’s erratic behavior as violent or as child abuse. Some are even wary of the registration process, fearing their children will be stigmatized.

Danny had gone missing before, but his mother was too afraid to call police, Bjes said. Building relationships with these families is key, he said, and a Spanish interpreter helped police gain trust with Danny’s mother and assure her they wouldn’t call Social Services. Ring donated a camera to help her keep an eye on Danny.

“Now she’d happily call us, and that’s the whole goal,” said Bjes, who works the midnight shift and has been on the force for nearly 20 years. “He’s a great kid, but he loves to run. He bolts, and he just goes.”

Bjes says his department is receiving more 911 calls of children wandering, or eloping as it’s also known, just as the number of children being diagnosed on the autism spectrum is continuing to rise. New numbers released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that one in 54 children in the United States are affected by autism, up from one in 68 in 2014.

A certified instructor, Bjes teaches other officers how to respond to a call for a missing child with autism, urging them to check bodies of water first. Searching for these children poses significant challenges for police because they often exhibit behaviors not seen in unaffected children. Many, like Danny, are non-verbal and unable to respond to searchers. Some are extremely sensitive to sound and calling out their name or using search dogs, ATVs or helicopters may drive them further away. They often seek out small enclosed spaces that may be overlooked during initial searches.

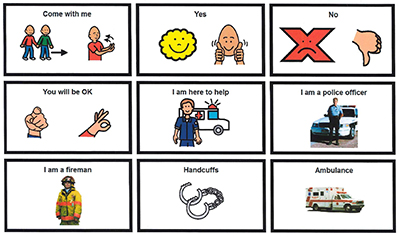

Special flash cards help police communicate with children who are non-verbal.

Teachers were using special flash cards with pictures to communicate with students who are non-verbal and Bjes wondered, why not police? Now, when Bjes and his officers respond to a call, they have the visual cards – What’s your name? Are you hurt? – in their police cars to facilitate communication. “They may understand what you’re saying but they can’t express it,” he said.

“My two boys are different,” said Bjes, noting that no two children with autism are alike. “The youngest needs headphones. He’s very sensitive to sounds. That’s a trigger. He’s the bolter of the two. It happened yesterday. I heard the front door and, boom, he was out the door.”

After their boys, now nine and 11, were diagnosed, Bjes and his wife learned everything they could about children on the autism spectrum. Because they wander, they installed a six-foot privacy fence, an extra security lock on the front door and a Ring camera, so they’d at least know in which direction either might be headed. He uses his own experiences to help officers “learn from my mistakes.”

Bjes is grateful that awareness about autism and wandering is growing across the country, but he’s striving for something more: acceptance. To that end, he coaches a special needs soccer program for ages five to 21 and every player is assigned a buddy – a police officer or a first responder. With each game, they’re getting to know the children they may one day need to protect, and the children are getting to know them. Most importantly, they’re realizing these are not just kids with special needs.

Said Bjes: “These kids are really just kids.”

For more information about autism and wandering, law enforcement search protocols and a list of resources for parents and caregivers, please visit, www.missingkids.org/theissues/autism.