Finding Missing Kids: It's in Our DNA

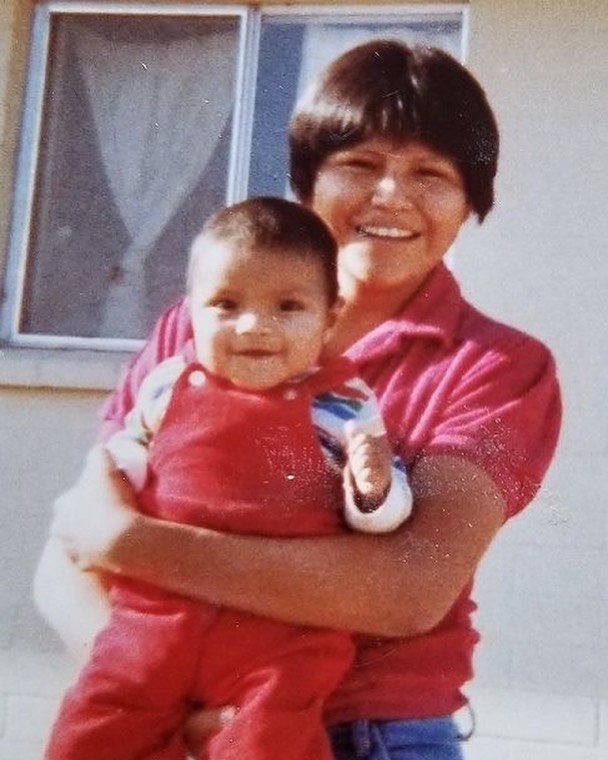

Peggy Elgo and her 1-year-old son were living with her older sister on the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation in Arizona when she vanished without a trace in 1983. With each passing year, her family’s hope of ever seeing her again, or even knowing what happened to her, began to gradually diminish – but never die.

Now, 37 years later, one of our partners, Bode Technology, has given Peggy’s family some long-sought answers. Using her family’s DNA samples, Bode positively identified Peggy as a Jane Doe whose remains were found in a remote desert area six months after the 19-year-old disappeared and 100 miles from where she was last seen. Her family still doesn’t know who killed her or why, but they’re grateful to be able to bring the Native American teenager back home to her reservation for burial. She’d be 56 today.

Peggy and her son.

“It was emotional for them,” said Phoenix Detective Stuart Somershoe, who delivered the news to Peggy’s sister and son. “Other relatives came forward and were thankful to at least have an answer to what happened to Peggy. DNA is what solved this case.”

At the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC), there’s plenty to celebrate on April 25, which is “National DNA Day.” DNA has become an integral part of our, well, DNA. Congress established the day to commemorate the successful completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003 and the discovery of DNA’s double helix in 1953.

Photos are still the most powerful tool for finding missing kids, but we’re using DNA more than ever before – giving families like Peggy’s some answers, finding children who may not have even known they were abducted, helping law enforcement identify suspects in child homicides and giving “living Does” who don’t know who they are their identities back.

“We’re using forensics to bring children home, and DNA is the number-one way we’re doing that,” said Carol Schweitzer, supervisor of NCMEC’s Forensic Services Unit. “We wouldn’t be able to do that if not for labs offering to help. Memories fade, witnesses die, families move away, but DNA doesn’t go away. It gives hope to any living relatives seeking answers.

Here at NCMEC, in the last 10 years alone, 238 cases of missing or unidentified deceased children have been resolved using DNA, Schweitzer said. Her team, which is currently working on more than 700 cases of unidentified deceased children, is also helping law enforcement with 25 “living Doe” cases. Four have been identified.

One of those was Carlina “Netty” White, who was abducted from a New York hospital as an infant. Two decades later, after having a child of her own, Carlina became suspicious when her mother could not produce her birth certificate. She began searching for her true identity and found an old photo of a missing infant on our website who looked a lot like her own child. DNA confirmed the child in the photo was Carlina, and she was reunited with her biological parents.

Carlina White

DNA became a game changer for us in 2004, when we formed a strong partnership with the University of North Texas (UNT) and its Center for Human Identification, the leading lab in the country providing free DNA testing through a federal grant to law enforcement and families of missing children. Since then, we’ve partnered with other federal, state and private labs, including Bode and DNA Labs International which are doing advanced DNA testing on the most challenging cases.

“We’re extremely thankful for the time these partners have donated, not just to NCMEC but to these families,” said Amanda Bixler, who coordinates DNA testing for us between the labs and law enforcement. She said no case is too old. “We’re never going to stop searching until we can bring these children home.”

Our team of retired law enforcement officers, known as Team Adam, have traveled around the country facilitating the collection of more than 2,370 DNA samples from family members with missing children. They’re then entered into CODIS, a national DNA database maintained by the FBI, to see if there are matches. Of the more than 126 missing children recovered using DNA, 110 were found by making direct comparisons with human remains; 16 were “cold hits,” meaning that proactively collecting DNA to load into the CODIS database resulted in a positive identification.

Phoenix Detective Somershoe said he was approached in 2018 by one of Peggy’s cousins, wondering if a Jane Doe, a Native American found the same year Peggy disappeared, could be her. The detective reached out to NCMEC for help, and obtained DNA samples from Peggy’s sister and son, which the UNT compared with the Jane Doe remains. “Our Jane Doe wasn’t Peggy,” said Somershoe.

Undaunted, the detective opened a missing person’s case and the UNT loaded the DNA samples into the CODIS database. It didn’t result in a match, but it did find possible similarities with another Jane Doe found in the desert in Pinal County, Arizona, about six months after Peggy went missing.

Bixler connected Somershoe with Bode, which was willing to try advanced DNA testing. They cracked the case. The lab positively identified Peggy as the Pinal County Jane Doe in January of this year.

Harnessing the power of DNA will give answers to more searching families, and the new frontier is forensic genealogy. Genetic DNA test kits, such as Ancestry.com and FTDNA, have become wildly popular with the public and are creating a robust database of family history in GEDmatch, where people can upload their DNA results and search for birth parents and ancestors. But law enforcement can only gain access to this DNA if people allow that to happen.

“It’s only as good as people who ‘opt in’ to let law enforcement have access to the database,” said Schweitzer. “We need the public’s help. It’s just that simple.”

And it’s working. Since 2016, forensic genealogy has helped resolve 18 of our cases – 12 unidentified deceased children, three living Does and three suspects in child homicides.

CeCe Moore, chief genetic genealogist for Parabon Nanolabs, recently helped crack a 35-year-old homicide case in Texas of a John Doe, whose remains were found on a ranch in Parker County. She learned the identity of the victim, and law enforcement was then able to determine who killed him. (See story here)

Last year, we began using forensic genealogy in missing child cases in an effort to locate children who were abducted to be raised, not harmed, like Carlina White. We’re hoping that some of these children, now adults, or even their children, are among the millions who’ve had their DNA tested, either now or in the future.

But we can’t do it without our partners and the valuable resources they provide. Their commitment and passion keep our mission moving forward. We want to give a special thanks to them on National DNA Day for helping so many families:

Bode Technology https://www.bodetech.com/

DNA Labs International https://dnalabsinternational.com/

Parabon https://parabon-nanolabs.com/

DNA Doe Project https://dnadoeproject.org/

Identifinders http://www.identifinders.com/

University of North Texas Health Science Center https://www.unthsc.edu/

Genealogy Consultant Barbara Rae-Venter https://barbara.genealogyconsult.com/

Kin Finders https://kinfindergroup.com/

California DOJ Bureau of Forensic Services Lab https://oag.ca.gov/bfs

Astrea Forensics https://www.astreaforensics.com/

HudsonAlpha Discovery https://www.dls.com/

DNA Solutions https://www.dnasolutionsusa.com/

Othram https://www.othram.com/

VA Department of Forensic Science https://www.dfs.virginia.gov/