Watching Your Child Grow Up in Pictures

When the email arrives, Colleen Nick steels herself for what she’s about to see. She dreads clicking on it “more than words can say” and prefers to be alone when she opens it on her computer.

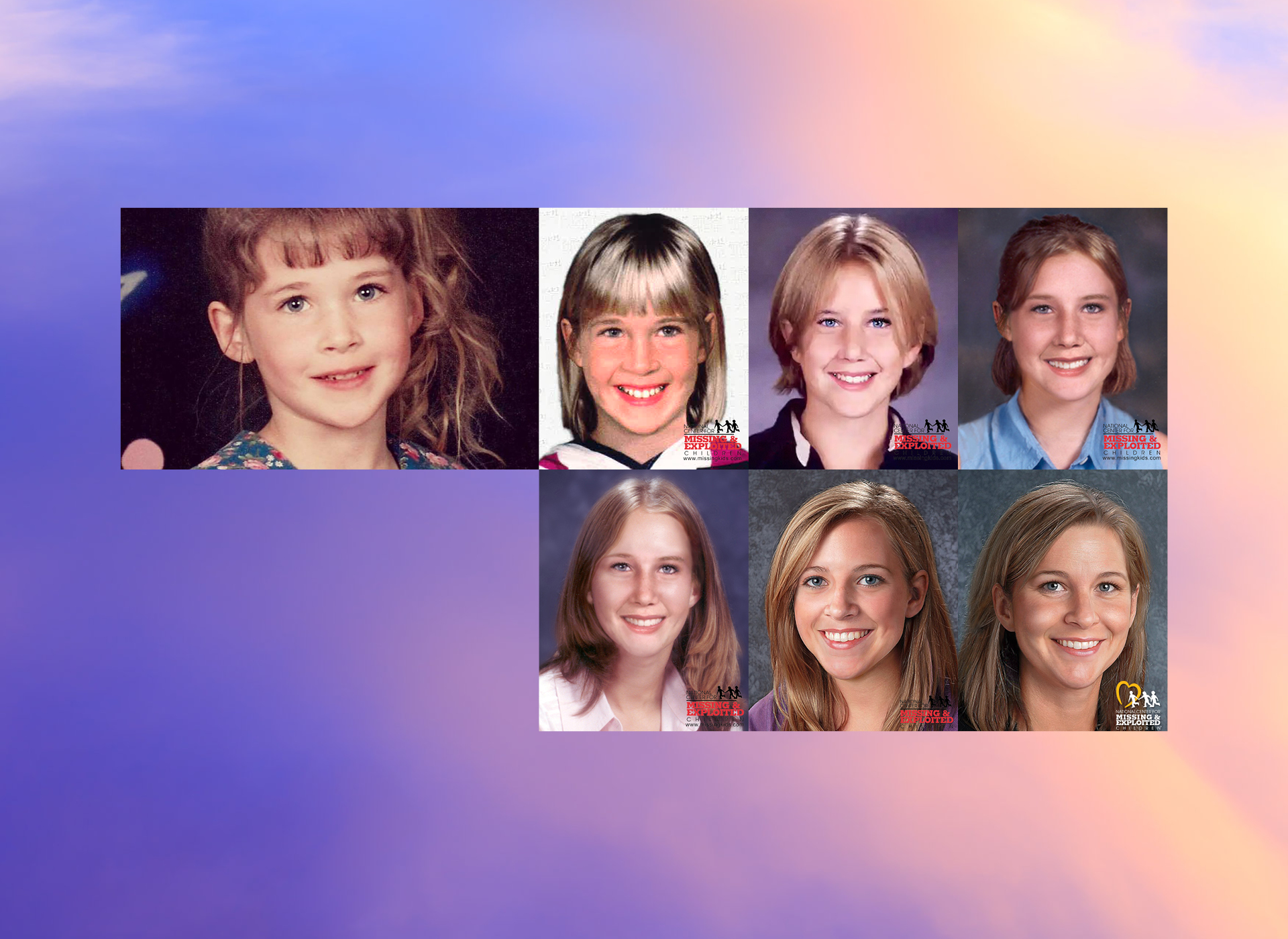

The email contains an image of what her missing 6-year-old daughter, Morgan, might look like today. On June 9, 1995, Morgan was abducted by a stranger at a Little League baseball game in Alma, Arkansas. As the game was winding down, the blonde, blue-eyed little girl threw her arms around her mom’s neck, gave her a big kiss on the cheek and scampered off to chase fireflies with friends. That’s the last time she saw her daughter. Today, Morgan would be 33 years old.

“It pierces your heart,” said Nick of watching her child grow up over the last 27 years through what are known as “age progressions,” which are created by forensic artists here at the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC). “I’ve always said that age progression is part of the hardest thing that we do with Morgan being missing. It’s a very emotional process.”

Six-year-old Morgan and her beloved kitten, Emily.

The purpose of an age progression is to show the public an approximation of what a missing child might look like as time passes, not just what he or she looked like when they vanished years, even decades, ago. The hope is that someone will recognize the age progression.

For families, age progressions are a double-edged sword. They give them hope of still finding their child after many years – but also pack an emotional punch.

“I can’t tell you how difficult it is,” said Pam Schmidt, whose 9-year-old granddaughter, Erica Baker, has been missing since Feb. 7, 1999, when she took the family dog for a walk and was never seen again. “We all recognize the value of the age progressions but also the difficulty of seeing your child grow up in pictures.”

Forensic artists at NCMEC have done more than 7,500 age progressions of long-term missing children, said Colin McNally, who supervises the Forensic Imaging Unit. So far, 1,800 children who’ve been age progressed have been recovered, some directly because of the AP.

Colin McNally, supervisor of the Forensic Imaging Unit, works on an AP.

McNally’s team of forensic artists digitally age a missing child’s photo on their computers every two years until they would turn 18, then every five years because a child’s features don’t change as much after reaching adulthood.

Our case managers work with families and collect photos of the missing child’s biological parents and siblings, ideally taken when they were the same age as the child would be now. The artists then create the age progressions, or “APs,” by merging features in these reference photos with the knowledge they’ve gleaned about how children’s faces develop and age over time, a process that takes about eight hours for each AP.

“Our team gets very attached to these cases,” said McNally, who will spend hours studying a child’s face before starting an AP. “We’re grateful we get to work on them, but we also wish we didn’t have to.”

When an AP is finished, our Missing Children Division sends a letter to the parent or guardian to prepare them:

“Although a valuable tool, we are aware that the initial viewing of this new image may be difficult for you and other family members. You may want to consider having a close family member or friend present when viewing the image for the first time.”

Families are advised that the AP won’t be added to their child’s missing poster for 10 days, awaiting approval from them and law enforcement. If families struggle looking at it, they’re encouraged to reach out to our Family Advocacy Division or Team HOPE, our peer support group of volunteers who either have, or have had, a missing or sexually exploited child.

Pam Schmidt

Erica’s photo age progressed to age 24.

Schmidt, whose granddaughter vanished almost 23 years ago, is part of Team HOPE and helps other families navigate the age-progression process. She offers to be with them on the phone when they open their emails to view the AP.

She tells them a new age progression is a way to get media attention to remind the public that their child is still missing. Families react differently when they open the email containing the AP.

“Some are absolutely devastated,” said Schmidt. “It’s hard to see your child like that. I tell them it’s very important to use every tool available, but they’re sad. Their lives have been forever changed. Not only for them but for everyone in the family. I don’t say it’s going to be okay. I say it’s going to be an opportunity.”

Marsha Gilmer-Tullis, vice president of our Family Advocacy Division, has helped many families over the years with age progressions, starting when they were sent through the mail, not on a computer.

Families are grateful that NCMEC never stops looking for their child, and the age progression reinforces the hope we all have that they’ll be recovered safely, Gilmer-Tullis said. Parents rarely meet or speak to the forensic artist doing their child’s AP, but the artists take each one to heart, she said, adding: “Their dedication cannot be overstated.”

On occasion, a parent will ask for changes to be made to the age progression, such as hair style or color, shape of eyes or complexion, or if they believe the child in the AP looks too young or old, Gilmer-Tullis said.

“Some parents say please don’t send them to me anymore,” said Gilmer-Tullis. “For them, the loss and memories are overwhelming.”

Duane Bowers, a licensed counselor who helps families of missing and exploited children, said it’s important to remember that the image can look like a stranger to families, especially when a child has been missing for a very long time.

“You’re looking at this and saying who is this?” said Bowers. “They didn’t do the aging with them. At some level, they always hang onto what the child looked like the last time they saw them. There’s no story to fill in.”

Nick gives herself a few days to process a new age progression before she shares it with her two adult children. She’ll also show them the reference photos so they can see what the artist used to produce the image.

“We’re no longer looking for a 6-year-old girl,” said Nick, who hopes her daughter will see the age progression in the media if she’s still alive. “What if Morgan sees this age progression on TV and she makes the call? It’s happened. Kids get recovered because they see themselves missing. So telling a child’s story, putting out an image of what we think they may look like could make the difference. It does work.”

Lost and Found Through APs

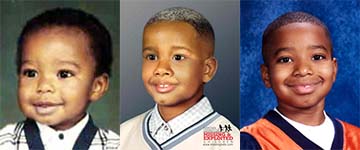

Daniel Markus, 2, was abducted in 2014 from Saint Lawrence, Pennsylvania. His AP was shown on the TV show John Walsh’s show, “The Hunt” after he’d been missing three years. He was recognized from the AP and reunited with his father.

Carlina White, 19 days, was abducted by a stranger from a New York hospital. When she was 23, she became suspicious about the woman who raised her as Netty Nance. She searched our website and found a photo of a missing baby and an AP that looked identical to her own child. DNA confirmed it was her.

Aric Austin, 2 months, vanished in 1981 from Vancouver, Washington when he was two months old. A federal Investigator recognized an AP of Aric on our website, and he was reunited him with his mother when he was 22 years old.

Joseph Carson, 3, was abducted by his non-custodial father and was missing for four years. A customer at an auto parts store saw his age progression on a TV monitor and recognized the child and his abductor who just happened to be in the store at that moment.

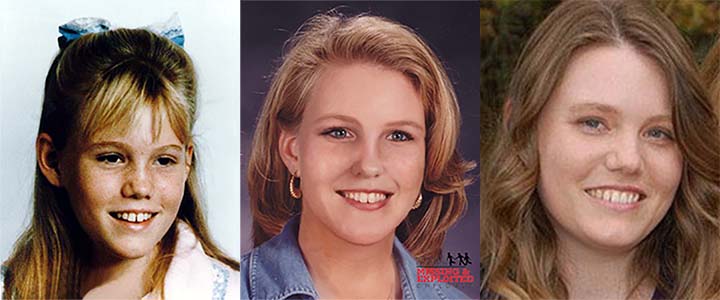

When Jaycee Dugard was recovered after 18 years, she and her mother came to NCMEC to thank those who had helped with her case, including Senior Forensic Artist Joe Mullins who did her AP. He teased her about her comments on TV that she didn’t think it looked like her. She pointed out that her hair is brown, not blonde as it was when she was abducted by two strangers as a child. On his computer screen, Mullins changed her hair color to brown. “That’s me!” she exclaimed.

Jaycee Duggard: Missing, AP, Found.

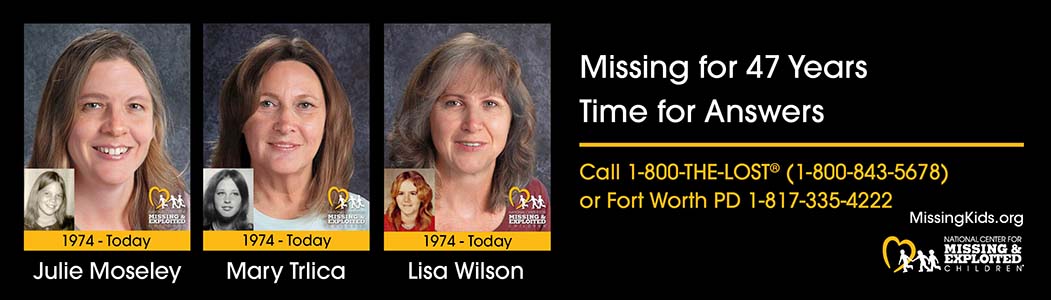

Nadine Dalley-Smith, one of our case manager supervisors, recently let Richard Wilson know it was time to do a new age progression of his 14-year-old daughter, Lisa, who vanished along with two friends, Mary Trlica, 17, and Julie Moseley, 9, while Christmas shopping in Fort Worth, Texas. Their car was found the same day in a Sears parking lot, but the three girls have not been seen since.

“It’s just like they’re still in that mall,” said Wilson, who was sent the new AP in the mail because he doesn’t use a computer. “It’s a really pretty picture, but I couldn’t swear it looks like her.”

That’s understandable: She’s been missing for 47 years.

Wilson, now 82, plans to frame an 8 x11 glossy of the age progression of his daughter, who would now be 61, and add it to his display of family photos of his grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

A billboard photo of APs of three missing girls.

Schmidt said, that in her case, the many age progressions done of her granddaughter over the years have helped the family in another way. The 9-year-old had begged her mother to let her walk their Shih Tzu, Jamie, in the rain and promised to wear her pink raincoat over her Winnie the Pooh sweatshirt and jeans. Panic set in when they spotted the dog with its leash trailing behind her – but not Erica.

“It’s really difficult to see,” Schmidt said of the APs, especially as more time goes by. “And yet there’s some joy that if we never get to see her again in this life, at least we know what she would look like.”