We never stop looking - Not even 55 years later

During the summer of 1966, President Lyndon Johnson, the Vietnam War and the skyrocketing price of the average home – $14,200 – were dominating the headlines. Getting much less coverage was the mysterious disappearance of a shy, 17-year-old girl named Jolaine Hemmy from Salina, Kansas.

Jolaine, one of 15 siblings in a close-knit family, was last seen working at a drive-in restaurant on July 1, 1966 when she vanished without a trace, not even picking up her last paycheck. Now, 55 years later, Jolaine’s nine surviving siblings, in their 70s and 80s, finally have answers they’ve been looking for more than half a century.

Her case, the oldest the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children has ever resolved, was finally cracked thanks to scientific advancements over more than five decades. But it took more than DNA testing and forensic genealogy to get Jolaine’s identity back: a police chief’s willingness to re-open a 55-year-old case, a few strokes of extremely good luck and the kindness of strangers on the internet who helped fund the effort.

“The most unbelievable thing is that somebody would really take that much time, energy, money to look for somebody,” Paul Hemmy, one of Jolaine’s brothers, told reporters after hearing the overwhelming news. “It’s good to know where and how and that she’s not suffering all these years.”

Our non-profit organization didn’t exist when Jolaine went missing. We were founded 18 years later, in 1984, and our first forensics team was formed 27 years after that to help law enforcement learn the identities of unidentified children who are found deceased. The team has two forensic case managers currently tasked with nearly 700 cases.

Senior Forensic Case Manager Ashley Rodriguez

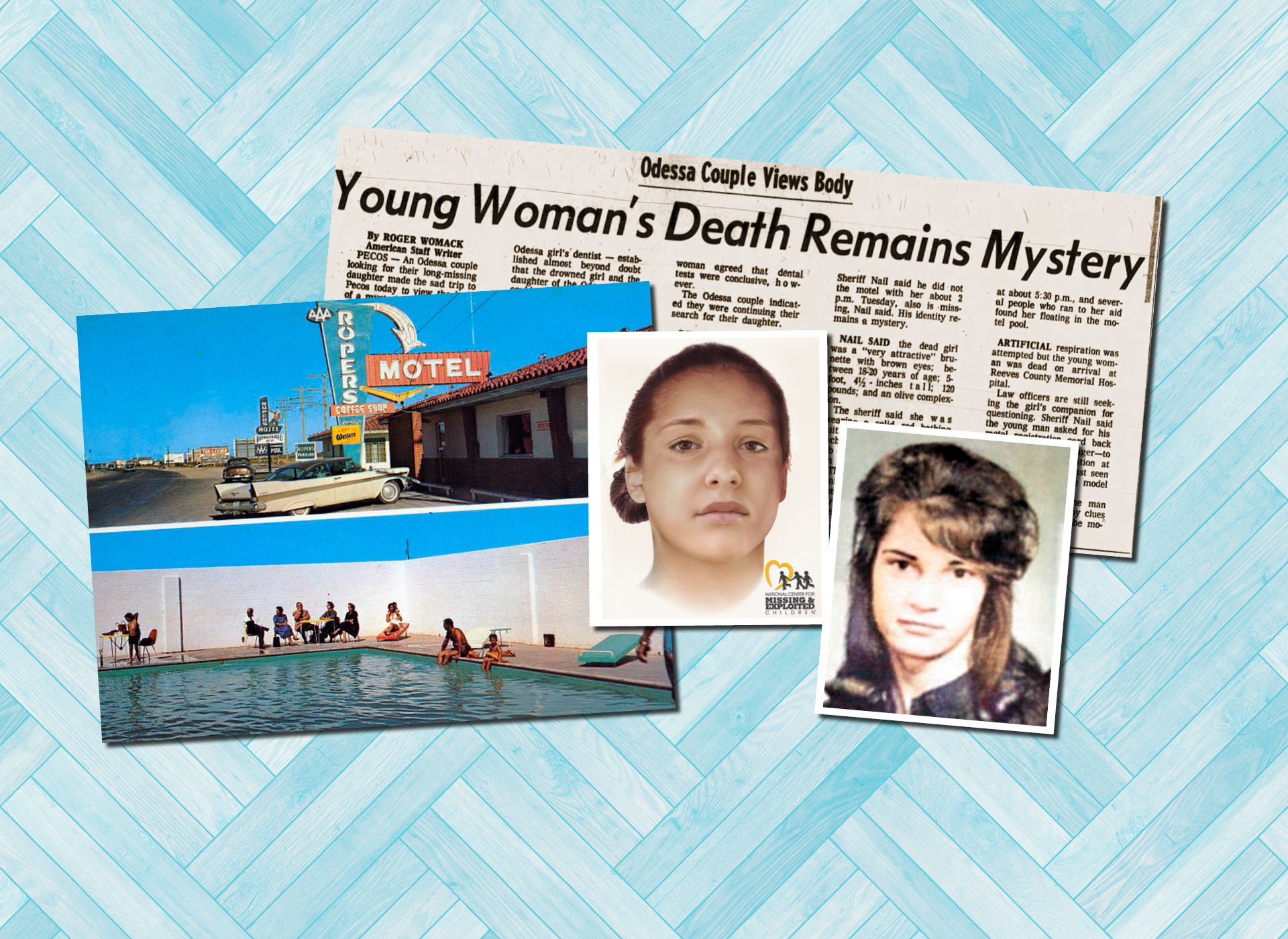

Senior Forensic Case Manager Ashley Rodriguez began working on the “Pecos Jane Doe” case in 2019. The only information she had to go on was gleaned from a few news articles that said Pecos Jane Doe appeared to be younger than 18 when she drowned under suspicious circumstances in a motel swimming pool in Pecos, Texas on July 5, 1966.

A married couple had checked into the Roper’s Motel in Pecos under the names Mr. and Mrs. Rusell Battoun. Descriptions of what happened next vary – some heard someone scream, others saw her husband in the pool with her – but what is known is that Mrs. Battoun was found unresponsive in the swimming pool.

While she was administered CPR and rushed to the hospital, the slim, blond-haired man she was with went to the front desk to retrieve their registration card which he said he’d need for identification at the hospital. He packed up their belongings, drove off in a late model sedan, presumably headed to the hospital, but was never seen again.

With little to go on, Rodriguez called the newly appointed Pecos police chief, Lisa Tarango. The chief wasn’t familiar with the cold case, of course, but was more than willing to see what she could find out and welcomed NCMEC’s offer of help and resources.

Police Chief Lisa Tarango holds press conference to announce identity of Pecos Jane Doe.

Anyone who had worked on the case, which was initially handled by the sheriff’s department, had since retired or died, so Tarango’s only hope was the local funeral home. Through a stroke of luck, an employee who was working there in 1966 was still working there in 2019 and remembered the case. Not only that, he knew where information about her burial might have been stored over the last five decades: in the funeral home’s garage.

Opening the file marked “Unknown X Girl” was like stepping back in time. The death of the young girl had clearly had a profound impact on the Pecos community, Tarango said. Along with the death certificate were letters written by strangers sending in whatever they could afford so she wouldn’t have to be buried in a pauper’s grave. News clippings in the file said her burial was delayed three weeks so “over a thousand families” could stop by to see if she might be their own missing child, she said.

“To me that was sad because it tells you there were a lot of missing children at that time,” said Tarango.

The funeral director and his wife had looked after her, donating a coffin, while a local dress shop provided burial clothes. When efforts to identify her were exhausted, she was finally laid to rest in the local cemetery, forever to be known on her headstone as “Unknown Girl Drowned” July 5, 1966. For as long as anyone can remember, flowers were left on her grave.

Strangers chipped in to pay for a proper burial.

Rodriguez and Tarango began discussing the possibility of exhuming the remains for the purpose of obtaining a DNA sample in the hopes of learning her identity. While Tarango sought a court order from a Pecos judge, a NCMEC forensic artist began working on a facial reconstruction using the faded Polaroid morgue and autopsy photos found in the folder, a daunting task.

Finished in time to mark the 53th anniversary of her death, on July 5, 2019, the facial reconstruction was released to the media in the hopes someone would recognize her. No one did, and NCMEC deployed one of its Team Adam consultants, a corps of retired law enforcement officers based around the country, to oversee the exhumation.

NCMEC facial reconstruction using 55-year-old photos.

Anthropologists from the University of North Texas took custody of the remains for a skeletal reconstruction and to extract DNA which they uploaded into CODIS, the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System, used to match known DNA samples, primarily in criminal cases. Still no answers.

David Mittelman, CEO of Othram Inc., a forensic lab in Woodlands, Texas, offered his company’s help. Othram specializes in working with trace amounts of degraded or contaminated evidence and has helped law enforcement close previously unsolvable cases.

Tarango’s police department had provided funding, but more money was needed to do additional DNA testing and forensic geneaolgy. An appeal was made to the public. The Pecos Jane Doe case was posted on the crowdsourcing website, www.DNAsolves.com. The money was quickly raised; people were eager to help Pecos Jane Doe get her identity back.

“A little bit goes a long way,” said Mittelman. As the prohibitive cost of testing has gone down in recent years, he believes modest donations, in the thousands, not tens of thousands, could help give names back to many more of the 700 children in NCMEC’s case files.

After Othram produced a DNA profile, NCMEC turned to Innovative Forensic Investigations to help locate any living relatives through genealogy testing. When a potential sibling was found living in Florida, law enforcement there went to the home and got a DNA sample, a mouth swab. Another company, Gene by Gene, compared that sample to Othram’s DNA profile. It was a perfect match. Her name was Jolaine Hemmy.

Video by Producer Amy M. Fallah

Tarango went to Kansas to personally deliver the news to family members, who were both shocked and grateful. They had searched hard for Jolaine and had never stopped wondering about her all these years.

“Talking to the family last week was like talking to them 50 years ago,” Tarango said at a recent news conference. “The emotion is as raw. ”

Now, the police chief has opened an investigation into Joaline’s death that occurred just four days after she went missing and more than 760 miles from her Kansas home. Was it an accident or foul play? Who was the male she was with and why didn’t he stick around when she was found unresponsive in the pool?

Tarango said Jolaine’s siblings don’t recall their shy sister having any boyfriends and can’t think of anyone she would have run away with. But they did share something that may be useful in the investigation.

Jolaine did not know how to swim.

#