Bringing Them Home

No matter how much pressure he was under, forensic artist Glenn Miller was unflappable, just as he was as a police detective. Always cool and calm –

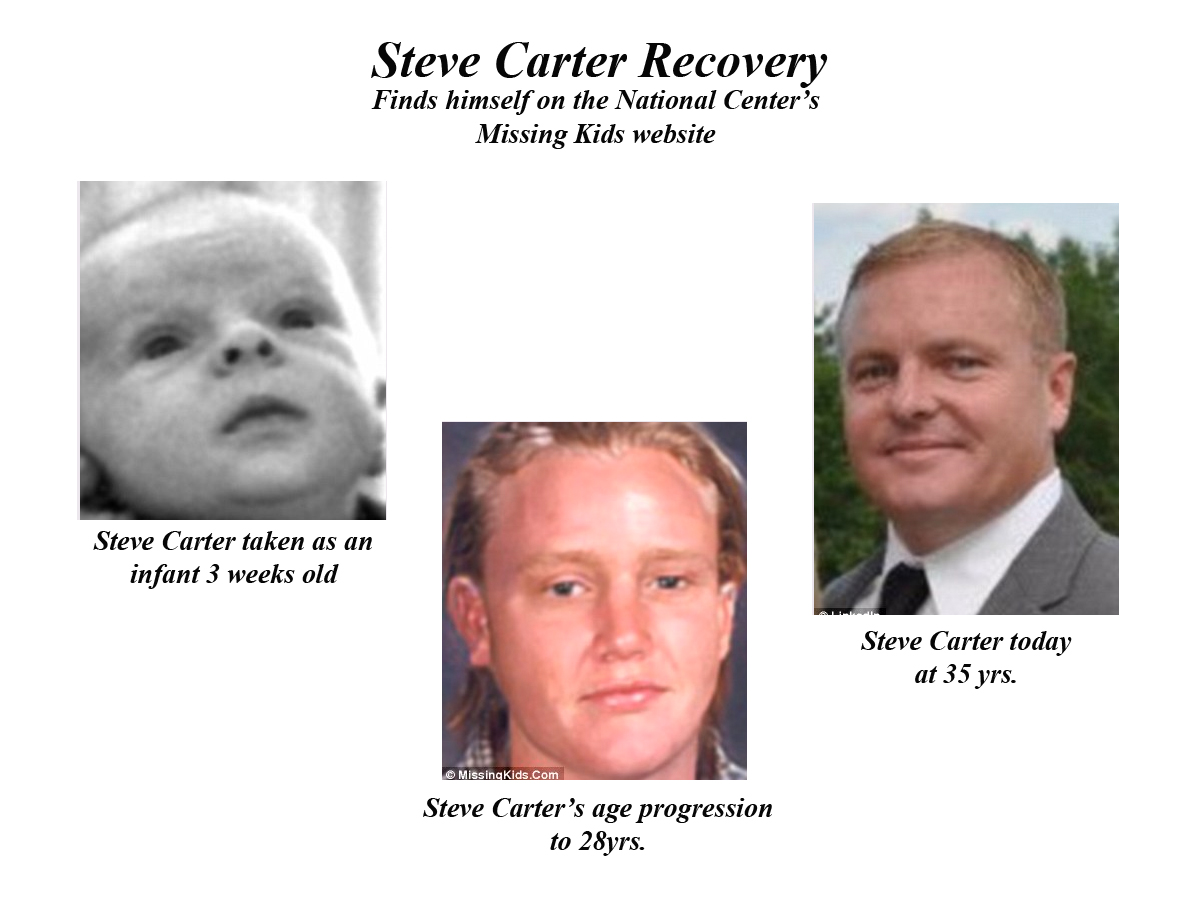

until one of his age progressions led to the recovery of another long-term missing child.

"That's what he was always striving for: to bring these kids home," Steve Loftin said of his former boss during those very emotional moments. "To be part of that – there's just no greater thing."

Today, the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children has a state-of-the-art Forensic Services Unit in great part because of Miller's leadership and vision. During his 20 years at NCMEC, before he retired in 2012, his small team performed thousands of age progressions and helped in the recovery of hundreds of long-term missing children. Miller became one of the nation's leading practitioners – and teachers – of age-progression technology.

Now NCMEC is mourning the passing of Miller, who died on Friday after a year-long battle with a rare form of cancer. He was 73.

"He was a pioneer," said Robert Lowery, who runs NCMEC's Missing Children Division. "We credit Glenn for the successes that we’ve had finding missing children.”

Miller followed his mentor and NCMEC’s first forensic artist, Horace Heafner, to the nonprofit in 1992 after retiring as a detective and forensic artist with Fairfax County police. In that job, he would create composites from witnesses' memories of bank robbers and rapists. At NCMEC, the focus was more daunting: He would age faces of long-term missing children in the hopes that someone may still recognize them years after they vanished.

Loftin, a fellow Fairfax cop who was hired by Miller to join NCMEC, said his boss understood the potential of computers and technology and helped develop the technique used today for age progressions.

"Glenn lived and breathed age progression for the longest time," said Loftin, who took over supervising the forensic unit when Miller retired. "It was his baby.

He was always looking for better ways to do it."

Using a combination of art and science, Miller would study the original photo of the child and family reference photos to create an age progression on a computer with Adobe Photoshop software. The goal was to produce an image that would elicit a spark of recognition from the public.

“For me, this job is very emotional,” Miller said in a 2002 People Magazine article about his ground-breaking work. “Every time I sit down to do an age progression, I remember that the picture I’m working from is someone’s little girl or boy.”

Miller was equally passionate about developing the next generation of forensic artists. One day he saw his neighbor, Colin McNally, carrying a portfolio and asked if he could take a look at his artwork. He was impressed by what he saw and invited him to take a tour of NCMEC.

McNally was studying artin college and had no idea he could use his skills to create age progressions to help find missing children. That tour led to an internship, then a job offer.

“He was a great example of how you can apply art to such a meaningful mission,” said McNally, who has been a forensic artist at NCMEC for nine years and became the forensic unit’s supervisor last year. “The impact he had on me – that’s why I’m stil lhere. Now it’s my passion.”

Joe Mullins with Glenn Miller

Joe Mullins, a senior forensic artist at NCMEC for 19 years, was the second person Miller hired after Loftin. “The Three Amigos,” they called themselves in their annual Christmas card. Mullins said no challenge was too great for Miller if it was something that could potentially help find a missing child.

One day, Miller was sent a child’s skull and asked if he could reconstruct it – to put a face back on it – in the hopes of learning the child’s identity. He had no idea how to do that. But he discovered someone at the FBI who did, so he sent Loftin and Mullins there for training. Loftin, now retired, and Mullins have done hundreds of skull reconstructions on their computers and brought long-sought answers to countless families.

“I love my job. I wouldn’t have it if it wasn’t for Glenn,” said Mullins, who also teaches the art of skull reconstructions. “I think of the thousands of kids who are now reunited with their families as a direct result of Glenn’s impact on age

progressions.”

As Miller was battling cancer, McNally would regularly check on his neighbor and mentor. Miller was eager to hear about new technological advances and recoveries of missing children. Even in retirement, McNally said, he could not contain his excitement about NCMEC’s mission, which was also captured in the article in People Magazine.

“People always ask us for the software that ages a kid from 10 to 12, but the computer doesn’t age a child – we do,” Miller said. “What I do is mechanical, but the outcome can be magical.”

Glenn is survived by his wife of 52 years, Gail Miller, two children, Jennifer and

Jonathan, his four grandchildren, two brothers and a sister. A celebration of

life will be held at Grace Baptist Church, 14242 Spriggs Rd. in Woodbridge on

Friday, Dec. 7. Visitation with the family will be at 9 a.m. with the service

to follow at 10 a.m. Burial at Quantico National Cemetery will take place at

noon. In lieu of flowers, contributions can be made to the National Center for

Missing & Exploited Children or to Dana Farber’s Neuroendocrine Tumors.