Boys for Sale, Too

When you hear that a child has been raped or sexually exploited, what’s your first thought?

That it was a girl?

Then you’re in good company. Boys are rarely on the radar.

“The rape or sexual exploitation of boys?” says Staca Shehan, who oversees the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children’s child sex trafficking efforts, “How often do you hear about that?”

That’s the same perception people have of child sex trafficking – that only girls are sold for sex, says Shehan. But NCMEC sees evidence of boys being trafficked every day, she says.

Using NCMEC’s missing children data, Shehan’s team recently analyzed a group of boys between the ages of 11 and 17 who were reported missing to NCMEC between 2013-2017, all trafficking victims or at high risk for trafficking victimization. The 565 runaway boys comprised 5% of all likely child sex trafficking victims reported to NCMEC during that five-year period.

Even though we know males are victimized by this crime, most child sex trafficking resources and public awareness campaigns today are still focused almost entirely on females.

“There’s a gap in knowledge with males in terms of having a large set of data,” says Shehan. “It makes it hard to get a true sense of how many male victims are out there if you don’t see them to begin with.”

It’s impossible to estimate how many children – boys or girls – are trafficked in the United States because of the hidden nature of the crime. Children sold for sex are victims, not prostitutes, and rarely report that they’ve been trafficked, especially boys. Many don’t even see themselves as victims or ask for help.

In its 2019 Annual Report, the United States Advisory Council on Human Trafficking says a “significant portion” of human trafficking nationally and internationally are boys and men, but there is a vast discrepancy in services available to them.

In NCMEC’s analysis of male victims, most were in the care of Social Services when they ran away, just like female victims. Half were white males, one fourth black and the rest biracial, American Indian or of unknown racial origin. Female child sex trafficking victims are disproportionately minority children.

Because most people who pay for sex with children are males, the advisory council also notes that “there is a common assumption that all girls who are victims of trafficking are heterosexual and that all boys who are victims are homosexual – further stigmatizing or labeling victims as a result of their trafficking experience.”

Also, boys are not trafficked in quite the same way as girls, so identifying and locating them requires new strategies, says Shehan.

Under federal law, anyone who buys a child for sex can be charged with sex trafficking – even if there was no third-party controller involved, such as a pimp.

Part of NCMEC’s ongoing training for law enforcement and child-serving professionals is to look for signs and to ask questions, because the children, especially boys, are not likely to disclose their abuse. Professionals may be less likely to think to ask boys, and so it’s hard to know with confidence how perpetrators target boys.

Currently, it seems more common for pimps who profit from selling their victims to others to be identified in the trafficking of girls, while that seems to be less common with boys, who seem to be targeted by those who exploit their vulnerabilities to get their basic needs met. Both boys and girls are also sold for sex by their family members or guardians. These factors can contribute to the trafficking of boys being much more hidden.

“Rarely do you see boys advertised, like girls, on classified ad websites,” says Sandra Berchtold, a supervisory special FBI agent assigned to NCMEC.

Nationwide FBI stings, such as “Operation Cross Country” and “Operation Independence Day,” have successfully recovered many child sex trafficking victims, but very few are males, says Berchtold.

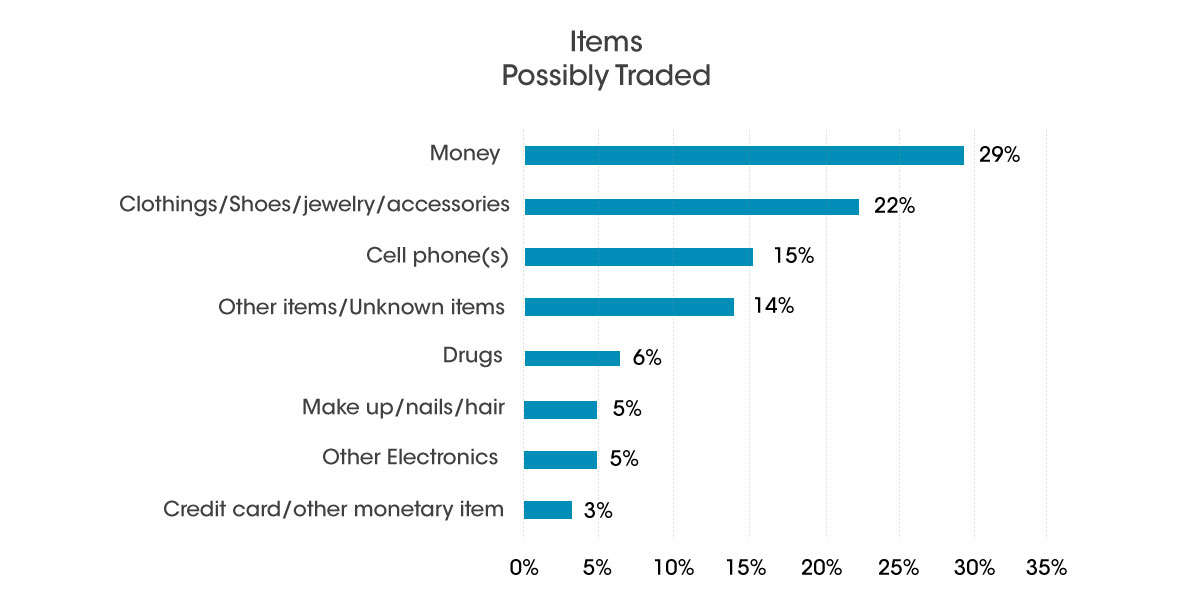

Moreover, trafficked children don’t always receive money for sex. In many cases, they’re paid with things they desperately need to survive alone in the world, such as food and shelter.

“What we’re seeing in a lot of these cases, regardless of the victim’s gender, is the perpetrators have something of value to offer – whether it be a place to sleep, money, drugs or numerous other incentives to win the trust of these kids,” Berchtold says.

With its veil of anonymity, the internet has created a thriving marketplace for traffickers, says Berchtold. Traffickers on the hunt for vulnerable, children not only approach them in person, but pursue them relentlessly on popular online platforms, including gaming, social media and video chat applications, she says.

“Even if you’re not on the streets and vulnerable, you’re in your bedroom and vulnerable,” she says of kids with access to computers and cellphones. One of the challenges law enforcement faces is making sure parents and victims know they’re not in trouble, says Berchtold. If you know someone is a victim of sex trafficking, please report it to law enforcement or NCMEC.

The NCMEC analysis of 565 boys also showed that, like girls, they also face a raft of other endangerments while on the run, including drugs and alcohol, mental health diagnoses, suicidal tendencies, special needs issues and carrying weapons. Many run away frequently.

Children who have been victimized by traffickers and buyers are survivors of a horrific crime, but that victimization doesn’t define them. The goal of identification and recovery is just the first step. These children are victims of a crime and are entitled to and deserve victim services. Male victims desperately need services, support and a safe place to stay, but they’re largely not getting them, according to Eliza Reock, NCMEC’s child sex trafficking strategic advisor.

“The number-one reason these kids are not getting the services they deserve is because they’re not being identified,” Reock says.

Some of the signs that boys are being trafficked are not unlike those for girls, she says: children carrying large amounts of cash or pre-paid credit cards, hotel keys and receipts and multiple phones. There may be evidence the child has been living out of suitcases or backpacks, at motels or in a car. The child’s ID may be held by another person, and tattoos may indicate money or ownership.

NCMEC provides “Hope Bags” to young trafficking survivors with basic necessities including toiletries, clothing and gift cards for food. While requests for male survivors has grown in recent years, Reock says she hopes as awareness around boys being trafficked increases, law enforcement requests for Hope Bags for boys will also increase.

“There’s no such thing as a safe missing kid,” says Reock. “Or that only females are trafficked.”

To read more about child sex trafficking, visit http://www.missingkids.org/theissues/trafficking