Who Would Steal a Baby?

Kindness was their M.O.

The women befriended new moms – one in a hospital lobby, another at a train station, a third at a carnival – and could not have been nicer.

The strangers fawned over the babies and offered to watch them to give the new moms a break. Grateful for the help, the new mothers stepped away. And they never saw their infants again.

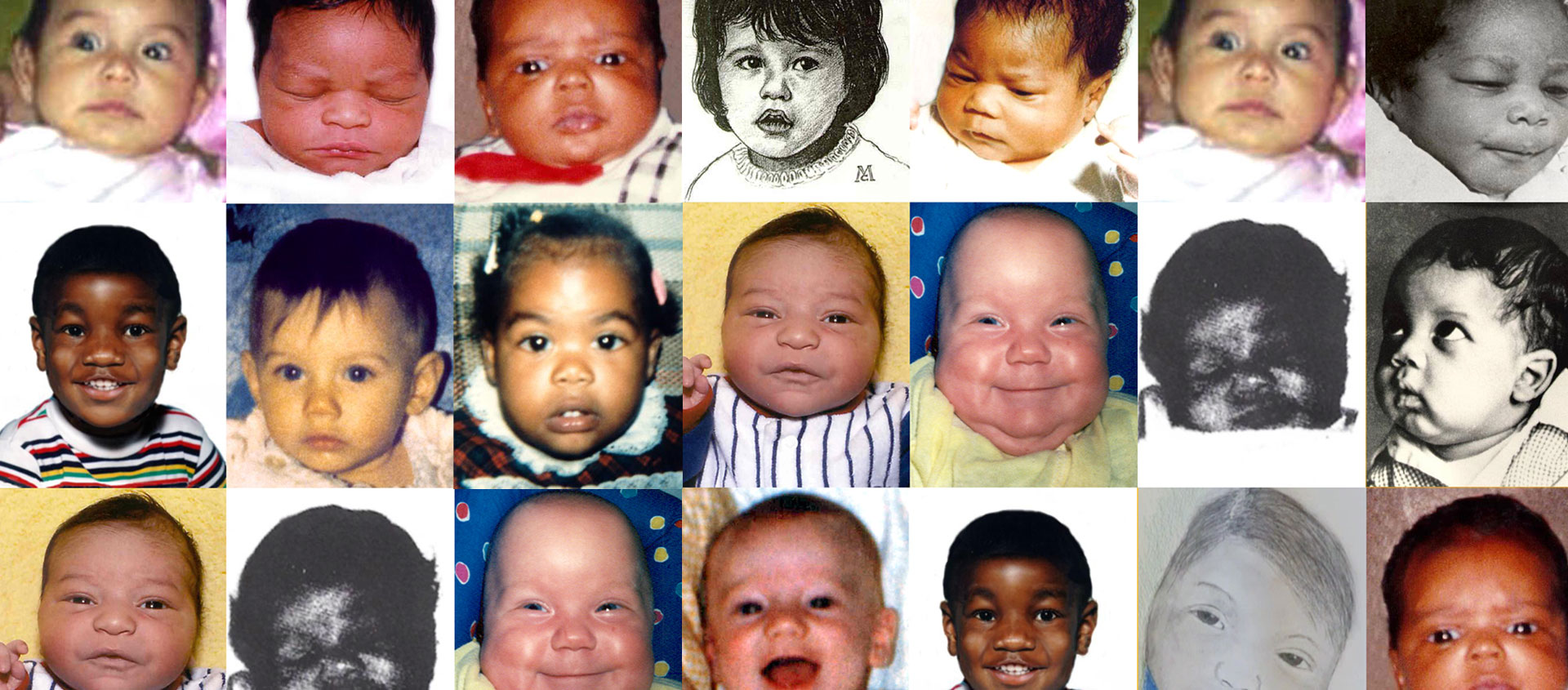

The infants were abducted in different states, at different times, during the 1960s through 2018. They are among 19 stolen infants who are still missing today.

Who would abduct an infant – and why? At the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, we wanted to better understand this rare and unique crime and analyzed these 19 open cases and 535 other non-family infant abductions that were solved or closed over the same time.

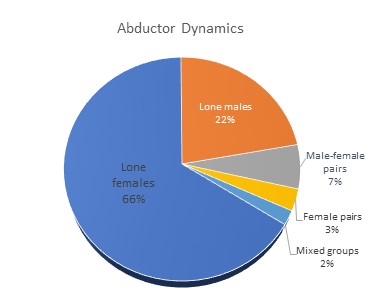

Among non-family infant abductions, most (62%) were committed by lone women of child-bearing age for maternal reasons: They wanted to raise the baby as their own.

Their personal circumstances varied. Some had suffered miscarriages or had a stillborn, lost custody of their child or their child had died. Others were trying to cling to a fractured relationship by pretending to be pregnant.

The vast majority of lone female abductors targeted very young infants, most often in the first few days of their lives. But some abducted infants have been a little older, even up to 1 years old.

The next largest group of non-family infant abductions (11%) occurred in the course of carjackings. In most of these cases, the carjacker didn’t realize there was an infant, or other young children, in the backseat. They often abandoned the children once they realized they were not alone in the car. They wanted a car – not a baby.

Retaliation was the motive in 7% of infant abductions. These abductors were trying to seek revenge or punish the infant’s parent, most often the mother. Sometimes infants were abducted in the middle of a heated domestic dispute.

The good news in our analysis: Nearly all abducted infants (97%) were recovered alive – and quickly – most the same day or the next. However, some infants were recovered long after their abductions, even years later as teenagers or adults. Three percent were recovered deceased.

Five-month-old Tiffany White was one of the lucky ones. Her parents were befriended by a 19-year-old woman from the Bahamas who would frequently visit friends in their apartment complex in West Palm Beach. She stopped by often,

always asking if she could hold Tiffany. Over several months, she became very attached to the pretty little girl.

One day in August 1986, Tiffany’s mother was putting her down for a nap when the young woman asked if she could take the baby with her to make a quick phone call. She wasn’t calling anyone. She was abducting Tiffany.

Instead of a phone booth, the young woman slipped into a waiting rental car with three friends and drove to Miami, where she boarded a flight to the Bahamas with Tiffany. Soon after arriving at her home in Nassau, however, she began having second thoughts. She flew back to Miami with Tiffany and turned herself into police.

“I thought I’d never see her again,” Annette White, Tiffany’s mother, said after her 30-hour ordeal in 1986. “I was going out of my mind.”

Like Tiffany, our analysis showed that more infants (39%) were abducted from their homes compared to a hospital or medical center (26%), a vehicle (16%) and various other locations.

But over time, beginning in 2010, there’s been a significant decrease (down to 6%) in abductions from hospitals. The shift correlates in part to NCMEC’s prevention efforts, led by John Rabun, to increase training, awareness and security.

“John Rabun recognized the trend at medical facilities and that there were striking similarities in the offenders in these cases,” says Robert Lowery, who oversees NCMEC’s Missing Children Division. “As a result, protocols were developed and hospital staff were trained on stronger measures to protect kids.”

Through a privately funded “Safeguard” program, Rabun, who went on to become NCMEC’s chief operating officer until 2012, personally did more than 1,000 on-site safety surveys at hospitals around the country and he provided nearly 70,000 medical personnel with trainings and consultations. Women of child-bearing age wanting a baby were literally “window shopping” in maternity wards and befriending new mothers or posing as nurses, he said.

New safety procedures and devices, including some used by the retail industry like anti-theft electronic tags, were adopted by hospitals to better protect newborns, Rabun says.

“John took a serious problem to a nearly non-existent one today,” says Lowery. “There’s nothing more joyous than seeing newborns, but the public is no longer invited to look through the glass in maternity wards. These offenders changed the culture.”

As medical facilities clamped down, NCMEC now sees most infant abductions occur in communities, some taken by violent force. Although rare, there’s been an uptick in C-section abductions, which account for the increase in the mortality rate. More than half of the 17 in-utero abductions in our analysis occurred in the mother’s home, followed by the abductor’s home.

Most abductors, our analysis found, were strangers or aquaintances who offered to watch the child or babysit. Some posed as nurses, social workers or photographers.

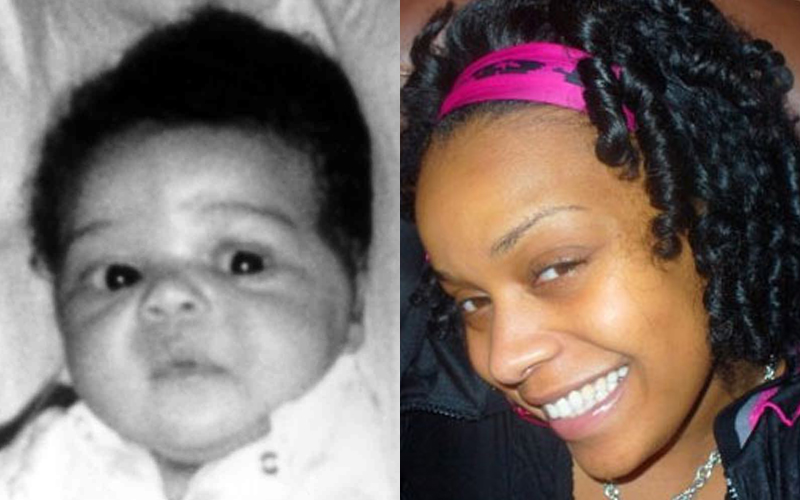

Carlina White then and now.

Carlina White was abducted from a New York hospital on Aug. 4, 1987. Security cameras showed Carlina being carried out of the hospital by an unknown woman dressed in a nurse’s uniform.

Twenty three years later, a 23-year-old woman named Nejdra “Netty” Nance called our Call Center asking for help in learning her identity. The woman who raised her had admitted she was not her biological mother but would not say who was, and Netty began a quest to find out.

Netty had seen Carlina’s missing poster on our website and thought she looked just like her own daughter. On Jan. 19, 2011 a DNA comparison confirmed that Netty was actually Carlina.

Abducted infants, of course, don’t know they’re missing. But at NCMEC, we’re seeing a growing number of abducted children who become suspicious, like Carlina and Steve, when they get older. Sometimes, it’s when they can’t get their birth certificate or they take genetic DNA tests to learn their ancestry.

While thankfully most infants are returned quickly, having a new baby taken for even a few hours or days is agonizing to the parents, says Lowery.

“I used to stay up at night worrying the phone would ring,” says Rabun, now an infant abduction response consultant for NCMEC’s Team ADAM. “I don’t have that feeling anymore. But we can’t get complacent with the progress we’ve made over the last 25 years.”